Looking around my kitchen, I notice many kinds of spoon—there are more than I thought. Ordinary ones for soup. Smaller ones for stirring sugar in my tea or eating yogurt. Ones of tiny Japanese ear-pick size for taking spices out of bottles. Chinese ones for dumplings will catch the soup coming out from inside, and it won't spill when you add soy sauce or vinegar. Such a spoon more or less plays the role of a small portable soup bowl. My favorite is the Mujirusi-Ryohin's measuring spoon. The handle is longish and firm, and won't warp if you measure spice and stir it in right away. Mujirushi-Ryohin has a line-up of some prominent designers for its product development. My measuring spoon must have gone through many trials and errors at the hands of those accomplished designers. So spoons can be a lot more than just spoons; they have wide variety and play many different roles.

We carry our spoons to our mouths with some liquid in it without spilling, almost every time we eat. But come to think of it, isn't it rather a difficult act? The cultural anthropologist Tim Ingold, in his book "Making", analyzes how we overcome those various difficulties when we eat cereals in the morning. First, we have to measure the right amount instantaneously, and scoop up the mixed lump of milk and cereal from a bowl with a spoon. Then we have to heave that "unstable gob" from a bowl to a mouth safely without spilling it. And THEN, we have to extract that spoon while closing our mouth and not drooling any milk. And it is not only about operating the spoon. Our breakfast table is full of difficulties. The distance between the table and the chairs, the body angle you maintain on your chair, and the positions of your plates—they all have to be accommodated to different situations to make perfect harmony. Ingold concludes from these situations that, by orienting yourself with “tools” such as tables and tableware, "you are designing the field of breakfast." It is not the manufacturers of furniture and spoons who are the designers, but rather the users who make up their own positions and orientations.

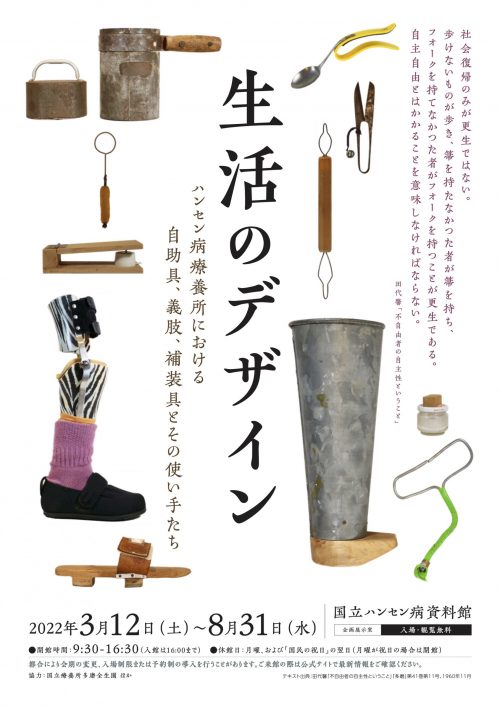

As of this moment at the National Hansen's Disease Museum, an exhibition called "Life Design" is being held. It introduces the self-help tools, prosthetic limbs and other prostheses that were used in sanatoriums, along with the people who used them. In the progressed stages of Hansen's disease, the patients are prone to injuries on their hands and fingers due to the paralysis of sensory nerves. Since they cannot feel the pain, their wounds could become aggravated and sometimes result in severance of fingers or legs. Some patients have their fingers bent or their wrists drooped, so called "hang-down hands." So in the exhibition room, there are spoons with holders on their handles or tips, ones with rubber wrist slings, or ones bent at different angles to make them easier to bring to the mouth. The symptoms and the degrees of the disease vary from one patient to another, so no spoons are identical. Every spoon has strong personality. These spoons have origin in an idea that is exactly the opposite to so-called universal design, which is intended for all the children, all the elders and all the people with disabilities of fingers or hands.

In the exhibition room there are more than spoons. We can see prosthetic legs, telephones with modified buttons for easier operation, teacups with urethane or different covers to avoid getting burned, a music box used by a blind patient to save money, and so on. Some of the prostheses exhibited are manufactured by prosthetists, and on video we can see how they get together with patients to make them easier to use.

Among these, it is very interesting to see the one showing how a patient called Mr. Kita gets a prosthetic leg made. He had been using one since his lower left leg was severed. But his legs were getting thinner with age, so he decided to get a new one after he had lost his eyesight to the disease. His prosthetist confides that it is his first experience of making a prosthetic leg for a blind person. If you can see, you can walk along while getting various kinds of information from your eyes. But when you are deprived of such information, how can you walk—and with what kind of prosthetics? According to the prosthetist, Mr. Kita has always been a "demanding customer" and his demands were always relevant to the problems at hand. The prosthetist says "it's worth trying as long as Kita-san is enthusiastic and we make efforts together." It is rather Mr. Kita himself who designs the prosthetic than the prosthetist, and the exchange between them in themselves played the role of blueprints for the prosthetic leg.

Another prosthetist says on video that he is not doing this for appreciation or gratitude, but just wants a patient to feel secure with him. To design a good spoon or a prosthetic, sometimes a designer might have to give up being a designer.